Follow the Data

Episode 2 | 54m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

Data has been an essential public health tool since at least the seventeenth century.

Data has been an essential public health tool since at least the seventeenth century. Helping the world understand and mitigate the spread of disease, data has helped us make sense of the threats to our collective health.

Follow the Data

Episode 2 | 54m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

Data has been an essential public health tool since at least the seventeenth century. Helping the world understand and mitigate the spread of disease, data has helped us make sense of the threats to our collective health.

How to Watch The Invisible Shield

The Invisible Shield is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

The Invisible Shield

Explore the discussion guide for The Invisible Shield, a useful tool for extended learning related to the docuseries. The guide pulls out key themes from the show and presents questions that encourage critical thinking, powerful discussion, and expanded understanding regarding public health.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipBattling a new pathogen is like a chess game.

There's the opening when the virus first emerges and very little is known.

The first case of the coronavirus has been reported here in the U.S.

He's currently quarantined at a hospital just north of Seattle.

And then there's the long middle game where you're using public health and social measures to try to shape the way the board will unfold.

In the early days of a public health crisis, one of the most important resources we have at our disposal protecting us is data.

I am calling in regards to your most recent COVID test.

If you can think back, when did you first start to feel sick?

Collecting data and analyzing and making sense of it and disseminating it has probably saved as many lives as the vaccines and the antibiotics.

Today, I'm announcing a two-week pause on our phased reopening plan.

This decision is based on the information that we've been able to analyze just in the last few days.

The problem is the data is not some completely empirical portrait of reality.

It's always evolving over time.

There is this big debate about whether kids should be in school or they should be learning remotely.

Essentially, every school district across the state is starting out this fall with distance learning.

But in Pierce County, it's not a choice.

It is the only county where local health officials are actually making an online start mandatory.

When I tell the schools that they have to close down, then I get hate mail from people saying "You're killing my kids."

When you make decisions on data and respond to the changes in data, that creates some frustration for citizens.

Pierce County Council is actually considering breaking up that local health department.

It means, in fact, we have a different governing body.

Now, I think that's a good thing.

Case counts show we are likely heading into the darkest hours of this pandemic.

Louder!

Now is not the time!

Now is not the time!

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ If there was a problem, why wasn't anything brought up to the health department?

We're tired.

Why did this come out of nowhere?

It makes no sense.

I rely on information from the health department to help me make decisions on how to run my general contracting business.

If one person dies because of this decision, you will have blood on your hands.

Quickly highlight a proclamation I signed today that is intending to protect the hard and vital work we're doing now in our local health districts.

This proclamation puts a pause, in effect, on efforts to terminate a health district or a city-county health department, +such as what is currently taking place in Pierce County.

Breaking news tonight, an ordinance to disband the Pierce County Health department fails to pass the county council.

I cannot be a party to having any kind of action taken on this manner.

I believe that it places the county at risk of criminal action against us.

Several hours of public comments on the topic overwhelmingly opposed the ordinance.

If you move forward with this ordinance, you will show yourself to be absolutely corrupt and undemocratic fools.

In a surprising move, the specific council member who tipped the vote was the ordinance sponsor, Pam Roach.

Yes, Council Member Roach?

No.

What?

Wait a minute.

And as you heard there, a big surprise coming from her.

No vote.

All right, yes, great news.

This pause will allow public health workers to focus their energies on the most challenging chapter yet of our pandemic.

Unfortunately, COVID was made into a partisan effort.

That hurt us dramatically.

There are heroes beyond counting in the COVID epidemic.

These public health officials have made decisions to save lives and keep people healthy even in the face of criticism.

You can restore your economy.

You can rebuild your business.

Once life is lost, there's no coming back.

So we made decisions that we thought that would actually save lives.

Attention train riders.

Masks are required by federal law.

And I have felt very steady confidence that they were made based on clear science.

The idea of using data to improve health outcomes on a society-wide level emerged in the 19th century out of a number of different converging forces.

Industrialization was happening so fast in England and parts of Europe and the United States, and urbanization was happening so fast.

London grew from less than a million people to 2 1/2 million people in a shockingly short amount of time.

Those changes were so dramatic that they had disastrous health outcomes.

This is total disruption that public health, not as a formal profession, but as a field, had to respond to.

More than anyone in that period, the guy named William Farr advanced the science of what was then called vital statistics.

Eventually became known as epidemiology.

And he turned it into really kind of an art and a science.

He built what were called life tables.

And he commissioned one extraordinary triptych of three different communities: British countryside, London itself, the metropolis, and then Liverpool, which was, next to Manchester, probably the most industrialized new city in that period.

What you saw when you looked at this visualization was just a scandalous, shocking, tragic gap.

People in the countryside were actually living close to 50 years on average, whereas in Liverpool, average life expectancy was somewhere around 25, maybe some of the lowest average life expectancies in a community that large ever recorded.

By assembling that data, he was able to prove that something was killing people in these large, new communities.

The tragedy of that news actually made it possible to imagine a positive outcome.

Like, if you can organize society in such a way to cause people to die at an accelerating rate, maybe you could make changes to society to actually reverse that and improve things.

These ideas led to the creation of sanitation departments, housing reforms.

Public health became a field that was dynamic in its conception of what health was.

And that that involves everything from infrastructure spending to data collection.

All sorts of groups began to try to figure out how we could have a new, industrial society that didn't create enormous gaps in suffering.

So it wasn't like a profession that just looked through a microscope.

In the fight against disease from a public health standpoint, it is fundamentally important to know when, where, in what numbers, and under what conditions various diseases are occurring.

We have now entered into the digital age.

We have the ability to now look at large quantities of data and make assumptions about the public health.

In February of 2020, we started hearing from local jurisdictions of excess mortality among African Americans.

And it turned out that that excess wouldn't be limited only to African Americans.

We've seen it among Indigenous people.

We've seen it among the Latinx population.

And these were not small gaps.

These were big ones with two, three-fold higher mortality risk.

And they were driven by the fact that people tend to be less healthy if they're African American as compared to white, so that if you got COVID, you might be in bigger trouble for a bad outcome.

One way to see the broad scope of public health is looking through the lens of the pandemic actually.

You can see how all of the inequities and health issues that people face from day to day that are not related to infectious disease have really put people at risk for severe COVID-19.

Anybody who has what we call co-morbid disease, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, is more susceptible to this disease and it tends to be more lethal.

Those patterns of diseases are racially and socially patterned.

Groups with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have greater burden of disease.

Poverty is a public health issue.

Poverty is a pathology.

When people live in poverty, it means that they die earlier.

It means that they get more cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Their kids get more asthma.

Communities of color tend to have higher concentrations of small particulate matter that lead to lung disease, to heart disease, to cancer, to low birth weight infants.

That greater burden of disease coupled with COVID made those groups more likely then to have death from COVID.

If people are able to live healthy lives, they have been much less affected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

And so it's about having people be able to lead healthy lives without disease that actually contributes to our success in controlling infectious diseases.

Not every challenge can be addressed by a vaccine or a medication.

Sometimes it's improving access to healthy foods, managing housing so that housing is safe, having a safe place to exercise so that you can stay healthy.

When you think about what's considered to be the most important point in public health history, you go back to 1854, to London.

1854, London.

It was horrible to be alive and a member of the working class in an industrial city in the middle of the 19th century.

There was tremendous poverty, tremendous problems with industrial pollution.

Childhood mortality rate is like 40%, 45%.

So almost half of your kids would die before reaching adulthood.

Maybe the most noticeable thing when you visited in London in the 19th century was just how smelly it was.

People did not have toilets attached to modern sewer systems and so there were cesspools in people's basements where they would just throw away their feces.

And then you would have these people called the night soil men who would come and collect the human excrement and dump it into the river.

And you had livestock adding to the smells.

Not just the horses, but people would keep cows in their attics for milk and things like that.

And then you had industrial pollutants everywhere.

So the city was an extremely unhealthy place to be.

And in some ways, that environment, particularly the smells, led, in a way, to one of the great mistakes in medical history.

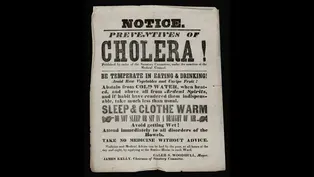

Cholera was one of the biggest killers of the 19th century.

It induced radical dehydration through terrible diarrhea.

People would just waste away over just 48 hours or 72 hours.

You could go from being perfectly healthy to being dead and you would be psychologically fully aware of it until the very end.

There are stories going around during the outbreaks of cholera in the 19th century that a husband would go off to work and then he would never come back.

And the family would find out, well, he just collapsed in the street in front of everybody in a kind of pool of diarrhea.

You know, it's horrifying.

At the time, people were under the impression that cholera was actually caused by something in the air.

The paradigm was that diseases that were contagious were spread through the air, through miasmas.

It was a reasonable assumption to make, the miasma theory of disease, of all smell is disease.

There was an early public health sanitary battle to remove the smells from the city.

In 1848, there was this act that was passed called the Nuisances Act.

There was a big movement to start installing these new water closets, these flush toilets that would wash away not just the contents, but the smells of human waste out of your home, out of your alleyways.

They just dumped all that stuff right into the river.

Into the Thames.

Of course, the Thames was the primary supply of drinking water for the entire city.

A modern-day bioterrorist could not have come up with a better scheme for poisoning the city.

And in fact, cholera got worse after this intervention.

That idea that cholera was something that you could drink was contrary to the paradigm of how contagions were thought to spread at that time.

What happened when this new disease came along is that we applied our old way of thinking to it.

You would see these cholera outbreaks where, you know, 10,000 people would die over the course of a few weeks.

And in the middle of all this is Dr. John Snow.

He was trained as a physician, came to London, began working in Soho, which was one of the poorest neighborhoods in all of London.

He was one of the first people to realize the importance of anesthesia, ether and chloroform, these gases that would relieve people of pain or cause them to go to sleep and you could then perform surgeries on them.

Snow had always felt that the miasma theory was wrong.

And he was an anesthetist, so he knew how inhalations worked.

He knew how gases moved around.

And he could see, look, this isn't something that you inhale.

Because if you inhaled it, it would make you sick in your lungs or your respiratory system.

Cholera made you sick in your gut.

At some point early in his research, he began to suspect that cholera was in the water.

He was trying to identify the organism that was causing the outbreak itself.

I mean, he had microscopes.

He was looking for it.

But the limitations of the lenses of the period prevented him from doing that.

But he was thinking on the microscopic scale.

He was also thinking about the scale of the human body.

He was also thinking about it on a neighborhood level.

And he was thinking on the scale of the city itself.

I mean, he worked on it for years.

And he actually built up quite convincing evidence to show that cholera seemed to be related to the question of where you got your water.

And no one really came around to his theory... Until an outbreak erupted literally on his doorstep in the late summer of 1854.

In a poor neighborhood like Soho, most people would get their water from these public wells.

There'd be a pump and people would go with a couple of buckets.

And they would collect water for the day or for the week.

And it happened there was a very popular pump right across from 40 Broad Street in the heart of Soho.

At some point, the well water became contaminated with the bacterium that causes cholera.

And this central watering hole for the entire neighborhood became a vector of death.

And within a few days, the single most concentrated and terrifying outbreak of cholera in England's history erupted in Soho.

And over the course of the next three or four weeks, 10% of the neighborhood was dead.

With an outbreak that concentrated, John Snow thinks there must be one source of water that is contaminated.

And if he can find that source, maybe he can finally convince the world that his theory about cholera's origins is correct.

Snow steps out into his community and starts knocking on doors, asking people, "Has anyone died here?

Has anyone gotten sick here?"

And, "Where did you get your water?"

But he also relies on public data that had been accumulated by William Farr.

Everywhere he looks, if someone has gotten sick as part of this outbreak, they had some direct connection to the well water at 40 Broad Street.

And based on that information, he starts to build a case for why the pump should be shut down.

And ultimately, Snow decided to represent all of the data that he and Farr had collected as a map.

It was a bird's eye view street map of the neighborhood with a little circle marking the well at 40 Broad Street.

For each death at each address, he put a little black bar corresponding to that death.

Because it was so concentrated, because it was so terrible, it enabled Snow to represent to other people this pattern that explained what was causing the death in the first place.

Snow presented his case to the local board of health and the pump handle was removed.

Within a few weeks, the outbreak was over.

It was one of the first cases where an actual intervention had been made by the authorities based on data.

And that led to a whole series of interventions to make communities safer over time.

After the 1854 outbreak, a number of major infrastructure changes were put in place to clean up the water supply for the city.

The most formidable of them all was the creation of the London sewers and really one of the most extraordinary engineering achievements of the 19th century, a massive project actually completed in a remarkably short amount of time, really about five or six years.

In 1866, an outbreak appeared in the East End of London.

John Snow had died about seven or eight years before that, but William Farr immediately treated it as a problem of contamination from drinking water.

He began investigating it.

And in a way, you can see that as the moment where the modern system of public health, of collaboration across disciplines from state institutions to infrastructure to individual medical practitioners reporting data, all of those things converged to stop this outbreak of cholera in 1866.

And that was the last time that cholera has appeared in London ever since.

It's not something the doctors did.

It's not something that the hospitals did.

It's something that, you know, a foreman did, bricklayers did, and civil engineers did.

You can see the icons of progress in the skyscrapers in some of the largest cities in the world.

But the developments that actually keep the citizens alive and healthy and living much longer lives than their 19th century equivalents would have, those achievements are all below ground.

That's what makes public health so powerful, that it's not just about imploring individuals to do the right thing for their health, but putting in place structures that mean that you get to be healthy without making a personal decision.

You get to drink clean water, breathe breathable air, eat healthy food.

These aren't personal choices.

These are protections that are made for all of us.

We've prospered because of public health.

It's what allowed us to build our cities.

It allowed us to have safe workplaces.

It's allowed us to really live longer lives.

One of the great breakthroughs in the history of public health and of medicine was the bacteriological revolution in which we began to identify specific germs that were identified with what we call diseases.

The sanitary idea of health had been extraordinarily victorious.

Tuberculosis rates were already declining tremendously, typhoid was declining, cholera was declining because we had put in the water systems and the air systems.

What it did was, in some sense, undercut older notions of disease as being broadly located in the environment in which people lived.

So public health departments increasingly turned to the lab.

We had narrowed our vision of what public health was, so that we began thinking of public health as a biological problem, which we had to use curative medicine to limit disease.

Medicine is a social science.

And our risk of disease depends on things like poverty, lack of education, hazardous working conditions, political malfeasance, all of these social factors that we now don't really think of as part of the disease equation.

We don't think of these factors because of the rise of germ theory.

This biomedical paradigm has influenced how we think about disease for the better part of a century.

It's why, when COVID arrived, so much focus went into things like developing vaccines or developing antivirals.

And very little focus was paid to the social conditions that allowed the virus to spread.

As we look at this COVID-19 pandemic, we knew that communities of color had more heart disease, lung disease, kidney disease.

Those chronic diseases put them even more at risk of getting really sick once they got infected.

The tragedy we had here is that our public health system had been weakened to such a degree that we weren't able to get our hands around it.

I think coming out of the pandemic, we now have seen real time what happens when you ignore public health.

A lot of people are going to die.

In the next minutes to hours to days, we're likely to see a million deaths reported in the United States from COVID.

This is a million reported deaths.

Of course, this is not necessarily the number of actual deaths that we know have happened.

That's actually greater.

But we are currently at 999,741 recorded COVID deaths in the U.S.

It's just been an incalculable loss.

These numbers are so big that it's hard to put a personal story behind each of them.

And it's really important that we remember that each one of those deaths has a story that goes with it.

We can't get numb by statistics, but that is a risk.

One day, you know, 3,900 cases and that's 3,900 people, right?

That's a human being.

That's a family.

That's a neighbor.

That's a coworker.

It's a neighborhood.

It's a community member.

Heck, it could be you.

It has been, quite frankly, a harrowing time.

What's, I think, more troubling to me, though, is how many people may have passed away that we may not actually be able to account for.

It is a chilling sight: a mass grave, rows of coffins, as burials quadruple in New York.

I don't even think we have an accurate estimate as to how many people we've actually lost in communities of color.

The need for infrastructure and public health includes the need for us to do a better job of data collection, so we actually know what's happening in communities.

If we can't measure it, we really can't manage it.

We need better health surveillance data in this country.

If you're missing data, then you miss whether or not there are pockets of illness and suffering that need special attention.

It is absolutely essential to understand the distribution of health problems and where they are the greatest in order to be able to fix problems.

We are only as strong as a society as our weakest link.

As we look back over the whole span of the COVID pandemic, the group that had the worst hit on life expectancy was the group classified as American Indian Alaska Natives.

Their life expectancy is now set at about 65 years, which is only met in our part of the world by Haiti, an incredibly troubled and poor country.

We'll turn to Ms. Echo-Hawk.

Thank you so much, Madam Chair.

My name is Abigail Echo-Hawk.

I'm a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma.

And I currently serve as the director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, one of 12 tribal epidemiology centers located across the country.

In addition, I serve as the executive vice president of the Seattle Indian Health Board.

I come from a tribal people who, at one point in time in 1910, there was less than 600 of us.

I want to start my testimony with a story.

Seattle was the epicenter of COVID-19 in February of 2020.

We quickly ran short of PPE.

We sent out requests to our state, our federal, and our county partners.

Soon, we received a box at our clinic and the CEO and myself opened up that box expecting to see gowns, masks, and the PPE that our providers need.

Instead, what we found was a box of body bags.

We had been sent a box of body bags instead of the PPE that we had requested.

While this was a very literal example of Indian health care funding and the way that we have been treated in this United States that has created the health disparities that currently exist for my people, it is also a metaphor for the way that many tribal nations experience getting resources for the COVID-19 response early in the pandemic.

The cumulative incidence of COVID-19 among urban American Indians is 2.03 times greater than amongst whites.

I would say one of the big drawbacks of this data is that only 46.4% of cases are arriving with race and ethnicity listed.

Yeah.

I really suspect that where the difference is greater for whites than it is for Indians, I suspect that that's not correct.

Aren't we missing Oklahoma and one of the Dakotas?

Yeah.

They are two of the only states that are not reporting race and ethnicity.

The calls that I've been on recently, I just was on one that was almost all county administrators.

And a lot of them were saying, hey, we have this data, and we've been reporting it.

And it's not our fault that the states aren't sending it correctly to the CDC.

We need to look at the overall American Indian Alaska Native population in North Dakota and Oklahoma.

I mean Oklahoma has a large-- some of the largest number of tribes of any other state as it was the Indian territories and they're not reporting?

As a result of the crumbling infrastructure of public health surveillance systems, we currently do not have the ability for both the states and the CDC to properly report COVID-19 data.

How data flows in the United States is complicated.

The main problem facing our domestic public health infrastructure is that it's badly outdated.

When the pandemic started, in my state of North Carolina, they were still making reports about cases of COVID in the mail and through fax.

You have to think of the public health information infrastructure like a piece of glass that someone threw really hard at the ground and it shattered into a thousand pieces.

And because it's a federated system with the control sitting at the state level, information doesn't flow well.

The CDC can ask for information, but there's no requirement.

You can't pass a law that says the federal government has to receive these data from the states.

And so what we have to understand is everyone was on their own throughout all of COVID.

We were working in silos.

And that's not a good way to fight a pandemic.

Many times, a data system in Chicago and maybe one in San Francisco, and another in Houston, they will code all the data differently.

One system may say male, female, M-F. Another one may say one-zero for male and female.

Another one may have a totally different designation.

And when you try to put that data together to create a national picture, if there isn't an agreement on how that data is recorded, there's no way to make sense out of that.

With more than 1,000 deaths reported yesterday, many states are struggling to contain COVID outbreaks.

Former CDC head, Dr. Tom Frieden, says to do that, the country urgently needs much better collection of data.

It's not the states' fault.

There isn't a national standard.

And the two crucial things that we don't have access to are what is our personal risk of getting infected with COVID if we go out and how well is our government and society doing in our community to reduce that risk?

If we're flying blind and we don't know how badly we're doing, we're not going to improve it.

There's so much in our community that we just don't see.

We need good data to make the right diagnoses and then come up with the right treatments.

The promise of better information is what can unlock our health.

Disease doesn't exist until we name it.

Disease can be all around us.

But until we say it's a disease, it can exist without any concern.

Who's dying and who's not dying, in some sense, determines whether or not the broader society, the professional community, recognizes this as a problem and recognizes it as a disease.

It used to be that we took symptoms of illness, people vomiting and getting fevers, as the symbol of what a disease was.

But today, we're beginning to realize that some diseases aren't what's called acute.

They don't just occur a few hours or days after we got exposed to something, but they actually may occur sometimes years, decades after we've been exposed.

They are noncommunicable diseases.

Noncommunicable diseases include things like heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic lung disease.

They cause 70% of global deaths, but they only receive 1.6% of global funding.

Many people think noncommunicable diseases are not preventable, but in fact, they are preventable causes of death.

In 1993, we wrote a paper on the actual causes of death and not what is the terminal event that's put on a death certificate.

What really causes people to die?

We went through the usual stroke and heart disease and cancer and so forth.

We found three things were responsible for 40% of all deaths in this country.

Tobacco was one of them, diet was the second, and alcohol was the third.

But no one actually puts that on a death certificate.

Public health and data are actually synonymous.

When you think about someone who is 16 years old, who picks up a cigarette and trying to connect that cause to cancer when they're 60 becomes much more difficult unless we think about how we create a data system that can track that.

Tobacco use affects all those leading causes of death that we're concerned about.

So we have an opportunity to affect a lot of serious chronic diseases when we do tobacco control.

People forget that you could smoke on an airplane.

We've now changed societal views.

When I lived in New York, you had second-hand smoke.

You had smoking in restaurants.

And now, it's not there.

We changed the environment.

I don't think there's anything that any of us that have been elected to serve the people of New York will do in our entire lives that will have the kind of impact that this legislation will have.

Talking about tobacco, we really worked on policy and taxes.

Those are the things that really get to change people's behavior.

You have to make a very conscious choice to go out in the freezing cold and smoke that cigarette.

Life expectancy in New York City increased by three years during the Bloomberg administration.

So much of our ability to make a difference has depended upon identifying a problem and critically beginning to move to do something about it.

Without action, public health data is sterile.

That was the significance of the work of John Snow.

Our public health history is really about identifying those pump handles and removing them.

We remember John Snow now because we like to have this nice story where our knowledge and our technology instantly kind of changes our behavior and puts us on this path of progress.

But you know, that's just a pretty story we tell.

When he died, he barely got a good obituary.

You know, he kind of became like persona non grata for insisting on his, you know, marginal, weird idea.

As a journalist and a writer, you're always interested in, well, how did the story begin?

Cholera is caused by a bacteria which normally lives in marine habitats.

It lives in kind of tropical, brackish waters.

The birthplace of cholera as a pandemic came out of most likely the Bay of Bengal in the Sundarbans region.

People didn't live in places like the Sundarbans for most of human history because these are places that are covered in marshes and mangroves.

It's flooded tidally every day, so half the time, there's no land there.

Humans did not interact with cholera-rich water for most of human history.

But then over the course of the colonial period in South Asia, the British Raj decided to cut down the Sundarbans, cut down all these mangrove swamps, turn them into rice paddies.

We can imagine that if you had a lot of farmers and fishermen living in this area with lots of cholera-rich water around, that bacteria from the water would have made its way into the human body.

The first cholera pandemic began in 1817 in the area of the Sundarbans and then moved with the bodies of traders and soldiers and travelers into parts of the Old World, into Russia, and then over into Europe.

New means of transportation brought the world tight and close together, making it one tremendous and congested city.

And that was the beginning of the first cholera pandemics in the United States.

When the cholera hit New York, and it was much heavier and affected more people than we expected, we explained it in terms of newcomers, the Germans, or the few Irish that were coming before the potato famine.

And we began to see that the evidence of cholera was strongest among those communities because they were living in horrifying conditions.

We ordered the population to go to church and pray on Sunday for God's redemption, but we didn't really do anything about it.

In the case of cholera, we understood that it was carried in the water years and years and years before we actually did the things that got rid of cholera.

In New York City, it took decades.

Private interests were much more powerful than public health actors and agencies.

And commercial entities didn't want to close down the canals, didn't want to close down the Hudson River, didn't want to close down the ports in New York City around Manhattan because that was bad for business.

They could see even at the time that cholera was clearly coming down those waterways and entering the city.

And quarantining would have been a reasonable response to that at the time, given what they knew, but they didn't do it.

Again and again, cholera entered New York City through the Erie Canal and the Hudson River, and the authorities in New York City didn't do anything about it at all.

And eventually, they stopped publishing any statistics about how much cholera was happening to such an extent that a group of just private physicians got together to say, "Well, we see all these cholera patients.

They're dying in our offices and our hospitals."

And they started publishing bulletins about what was happening.

Left on Abigail.

So in thinking about this data issue, I think, is a lot more complex than even what's being discussed right now.

My organization put out a report titled "Data Genocide" that looked at both racial misclassification and also how states were not reporting race and ethnicity around COVID-19 case study data.

We are effectively not including these populations that is directly contributing to the COVID infection rate.

Every single day, I'm fighting for the visibility of our people.

The erasure of Native people through data is what I consider a cultural genocide by the United States government where they no longer have to fulfill treaty rights because we can't even prove we exist anymore.

As an urban Indian health program, as an Indian health care provider, we have a treaty right to quality health care.

And yet, the Indian Health Service has always been chronically underfunded, funded in between 30% to 40% of known need.

When you think about public funding, you fund what you know.

And if there are no data, then there's no information.

If there's no information, there's no problem.

And if there's no problem, why would you fund it?

So if we can't get the data we need to understand the challenges we have, we'll never be able to muster the political will to actually confront those issues.

We decided that we were going to do a report card of every state in the nation on how well they were doing in reporting race and ethnicity of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

This was the closest number we could get for the number of Native people, and we recognize that this is an undercount.

The state of Washington received a C. And that's because it was doing good in two areas.

It got an A-plus and then 100%.

And then it was absolutely failing in the other two areas.

I think we have to be honest that data systems, if they do not utilize an equity lens, then they miss out on so many people.

That's a problem.

And I tell you that from a-- you know, from a Asian American standpoint.

I mean, if you think about Asian Americans, we come from so many countries across the globe.

And yet when you say the word "Asian American," it's almost as if it's a one category.

But I will tell you the health needs of South Asians, very different than the health needs of Southeast Asians.

But we aggregate and we clump and we put people in categories, in buckets.

And then we turn around and say, "Well, there's not a problem in your community."

Shame on us.

Of course there's a problem in the community.

It's because we have aggregated you, so we have masked your inequity.

I did hear from Washington State within two days of publishing this report, and they want to work with us.

And we're beginning to start meetings with them so that they can begin to report race and ethnicity better.

Decision making, it can only be done robustly if you have robust data systems that are strong, they're sustainable, they're strategic, and ultimately, that they work for all of us.

We have to do better by our people.

Sometimes they describe epidemiology as individual stories with the tears washed away.

People want to know what the data is.

But what moves them to change things in our society is what has happened to them or their neighbors or their children.

I just can't ever accept body bags for our people.

I needed to be able to reclaim this body bag into something that was of joy, of healing, of strength, and resiliency.

Each of the ribbons represent prayer.

Here on the sleeves, I had started to work.

And I got a text from a friend of mine to tell me that a mentor and a dear friend had passed on from COVID-19.

He wasn't old enough to be lost this soon.

And so I picked up the dress and I decided to incorporate the toe tags.

And on here, you'll see that there's jagged stitching.

It represents the marks that you would see on a body from an autopsy.

This is something I say to myself all of the time: I'm a tangible manifestation of my ancestors' resiliency.

All of the statistics that we've seen around COVID-19, around other health disparities, lose the people and lose the story.

Every data point is a mother, is a father, is a son, is a grandparent.

And this dress represents to me data.

Data is an Indigenous value.

It's not just a statistic.

It is a traditional way of us using information to improve the health and well-being of our people.

Most of our data modernization can be done through installation of computers and software and really the modern tools that we use in our everyday lives that haven't made it to most state and local health departments.

There is a $1 billion program called the Data Modernization Initiative that is upgrading our nation's public health data infrastructure and really trying to bring it into the modern era.

There have been some very promising developments that enables data to flow from electronic health records into public health systems seamlessly in an automated way.

We have the capacity if we're willing to invest the resources to automate as much as possible so that our frontline epidemiologists can get information that's up to the minute.

I think about how we get the weather forecast on our phones every day and how we use it to make decisions without even really thinking about it.

The National Weather Service is a many decades old institution that has evolved over time.

And it has evolved with investments in data, in people, in analytics, in scientific infrastructure.

And I think someday, we might get to the place where we do something similar with infectious disease forecasting.

I can imagine a world where I decide whether or not to grab a mask before I commute on the metro or whether that birthday party actually needs to be outside and not inside because there is a virus circulating in our communities.

And I think we really are at the place of creating this infrastructure.

I think the promise of data in terms of health care and in terms of pandemic control is a real one.

If I'm willing to share my location, the list of the people that I've interacted with from my cell phone that pings with someone else's cell phone, maybe we can actually stop a pandemic in its tracks.

The speed with which we're sharing information is beginning to approach the speed with which the pathogens move.

We now have the capability through cloud computing and artificial intelligence to really apply these new sciences to public health.

The anticipatory modeling of future outbreaks requires tracking people that are flying around the world, that are going into assisted living facilities, into and out of hospitals, day care facilities, so that you can potentially understand where that disease might be going next.

That idea of turning the world into data in the name of these efforts to prevent outbreaks, to a lot of people, it seems like we're losing our privacy.

When we talk about data, people often think of it as almost dehumanizing.

People need to know that we get concerned and worried about these numbers because they are real people.

It dates back to the bills of mortality.

When you die of leprosy and they put you on the bill of mortality as one of the seven people who died of leprosy that week, you have become a number.

In your dying moments, you are recorded and registered and distributed as a data point to be analyzed by the authorities.

In a sense, it was a kind of Faustian bargain that we made that, you know, we will surrender this data about our health so that we can live longer lives.

We doubled overall human life expectancy in part because of the data that we collected and the patterns we were able to see in that data.

A public health data system that is built upon privacy and security is absolutely essential, first of all, to be successful in identifying and stopping disease outbreaks, but even as important, to maintain the public's trust.

Corporations have much more data about us than the state.

Especially in the United States today, people are much more willing to give up that information to the Amazons or Googles of the world.

And it's information they would never dream about giving to Donald Trump or to Joe Biden.

These corporations don't necessarily have public health in their interest.

We need to restore the idea that the central authority responsible for protecting people's health is government.

Over the past 24 hours, more than 3,000 deaths from the virus have been reported across the country.

That is larger than the death toll on 9/11.

Governor Jay Inslee's office has confirmed the governor will be holding an 11:00 news conference tomorrow to outline a new set of restrictions.

Inslee has overstretched his authority.

We cannot allow one virus to destroy this Constitution!

There is a natural tendency, I think, to be suspicious of power or authority, especially if it's talking about something that's invisible like viruses.

But there is also enormous consequence for resisting public health authorities.

It became clear well into the COVID pandemic that one of the main factors affecting deaths and other outcomes was the level of trust between the people and its government and between people and each other.

We do really well with passive public health.

We do really well when there's a policy that's passed that you don't have to actually do anything to participate in the safety that you get.

But to ask you to wear a mask, that's a more active version of public health.

And that's where we're finding the greatest resistance.

A lot of people don't want to wear masks.

There are a lot of people think that masks are not good.

Many politicians have told us for the last several years that your health is in your hands and that things like masks or indeed vaccines were about lowering your individual risk, when, in fact, we needed to ask, "What is my contribution to everyone else's risk?"

This dichotomization of us and them actually completely hampers our ability to be safe.

The real threat is the pathogen and the way we respond to the pathogen.

Everything we're seeing through the COVID pandemic is just symptomatic of a broader disease of mistrust and a distrust of government.

It's the same disease that led to the January 6 riots.

Just as Trump supporters breached the nation's capital today, a local group of protesters surrounded the governor's mansion in Olympia.

We paid for this mansion, so yeah, we're taking it over!

Certain people feel like public health or the well-being of others or even our responsibility to not spread a contagion was not the number one thing to be concerned about.

You do not get to keep your authority when you take our rights!

I revile these acts of sedition and intimidation that we've seen in our nation today.

But those acts of intimidation will not succeed in any way, shape, or form.

We will continue the work we're doing to protect the health of Washingtonians.

You can smell smallpox before you enter the room.

The pus ends up giving a stench of decaying flesh.

The eradication of smallpox was one of the seminal achievements of the last century.

I see vaccines as the very foundation of public health.

A vaccine is just a product.

And it is useless without vaccination, which requires social trust.

Smallpox disappeared so fast because they trusted us.

The amount of vaccination we're doing is not enough to bend the curve.

I was sharing with the church, you know, when the vaccine come out, I won't take it.

The trust level is broken.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Cholera and the Modern Public Health System

Video has Closed Captions

How the 1854 cholera outbreak led to the birth of the modern public health system. (1m 12s)

Video has Closed Captions

Steven Johnson describes the origins of cholera and how interventions stopped the spread. (2m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

Data has been an essential public health tool since at least the seventeenth century. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship